Britannia Mine Museum is a new industry member of the BC Association of Travel Writers. I make a visit. Just 55 kilometers north of Vancouver, and ten minutes south of Squamish, the Britannia Mine Museum is easy access along the scenic Sea to Sky Highway 99.

At the site of what was once the largest copper-producing mine in North America, Britannia Mine Museum is at the head of Canada’s southernmost 42-kilometer-long inlet/fjord. Mill 3 has 14,416 shiny windows overlooking Howe Sound. Meet the Concentrator. It crushed Mill 3’s ore into concentrated powder. We’re magnetized…

And yet, the question is like a fault deposit in my veins I can’t extract. How can the British Columbia government state that what was one of the “largest metal pollution sources in North America – having significant impact on local waterways like Howe Sound and the Squamish River” still be an award-winning museum today?

The History

The answers lie in history and in the museum’s mandate as a registered charity, a National Historic Site and a BC Historic Landmark.

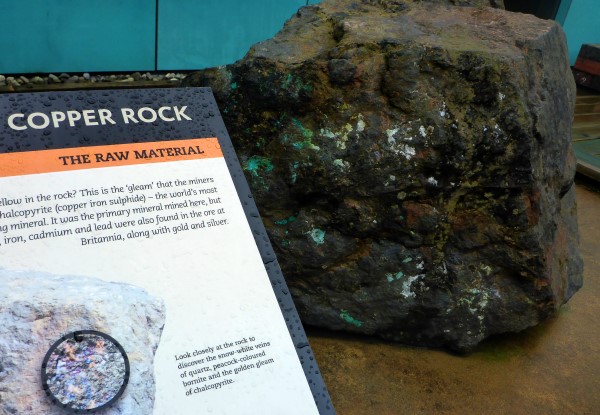

Going back to the turn of the last century, the mine opened in 1904 and extracted a multitude of ores (mainly copper).

It closed in 1974. The worst impacts were still to come.

Impacts

Shafts (210 kilometers of them) from the open pit mine at the top exacerbated a natural process called Acid Rock Drainage (ARD). Once sulphide minerals came into contact with water and oxygen (rain and air), the ground water coursing through the tunnels became acidic.

An exhibit entitled ‘How Weird is Water?’ explains a bit about how solvent water is. How its basic neutrality can be altered.

“More materials dissolve in water than in any other liquid…it is the ratio of H+ to OH- (H being Hydrogen, and O being Oxygen) which defines the acidity of water. Neutral water contains the same amount of each, where acidic water contains more H+ ions.”

The Solution

Since the opening of Epcor’s Water Treatment Plant in 2005, diverted water collected and neutralized. An 8-m thick concrete plug blocks the Howe Sound portal. With those applications in place, 2011 saw the first returns of Pink and Coho salmon in over a hundred years.

We arrive in time to take one of the hourly 45-minute tunnel tours. We hop aboard the train with our tour guide, Emily, and some other information panners.

Going Underground

“I’ll take you underground and show you some of the conditions the men had to work with…watch your step…they never had overhead lights.”

“We’re a hard rock mine. Holes were drilled into the rock, filled with dynamite, and blasted (after hours)…in 1904, they used the wood drill…called ‘the widow maker’ due to the inhalation of silicon dust…(Later), the stoker drill with a water hose (then) the jack light drill in the 1930s reduced the dust further…watch for yellow outlines…find your bull’s eye, drill 30-35 holes, and get out.”

“Muckers…shoveled that rock over (the) shoulder…two men had to move sixteen tons of rock in one shift, just like the song ‘Sixteen Tons …and whaddya get, another day older and deeper in debt.’ We hum along.

Copper ore is heavy, dense rock so the shovels had small blades with short handles until mucking machines came along. Emily revs up the mucking machine.

“Cover your ears; it’s a little bit noisy.”

“You would spend your entire eight-hour shift underground; wet and dirty… with only a light that you would carry with you…in 1904, that was a candle…in 1919, the carbide lamp was introduced…clip it to your woolen cap (no hard hats yet)…the first battery lights weighed 16 pounds.”

Emerging

We emerge and enter Mill 3 where Emily explains how the ore was crushed “into very fine sand…95% waste, and to separate it out, we used a giant froth separator, a giant bubble bath for minerals.”

We walk back along the boardwalk to the gold- panning area. Families try their hands.

There’s a Mining A-to-Z film, an interactive exhibit for your-inner school child, and glittering minerals on display. Truly a delight for kids and adults alike, we watch this hands-on experiment.

Times have changed. Industry, informed by technology and good governance, may prevent serious oversights of the past.

Moving Forward

Patricia Heintzman, Squamish mayor since November 2014 wants to make Squamish renewable.

In a ‘Mountain Life’ article entitled ‘The Life and Hard Times of Howe Sound’ she says there’s “still some appetite for industry, but it should be clean. Where everyone draws that line is debatable (without going) back to the air and water quality issues that plagued Howe Sound for 50 years.”

Or, leave it to Charles Dickens:

Pip, dear old chap, life is made of ever many partings welded together, as I may say, and one man’s a blacksmith and one’s a whitesmith, one’s a goldsmith, and one’s a coppersmith. Divisions among such must come, and must be met as they come.

Britannia Mining Museum keeps mining ways to make us clear-eyed miners of information, learning from the past, forging our future.

Uncover a warm cocoa coating from Galileo Coffee Company (the principal decor of the Britannia Brownie)